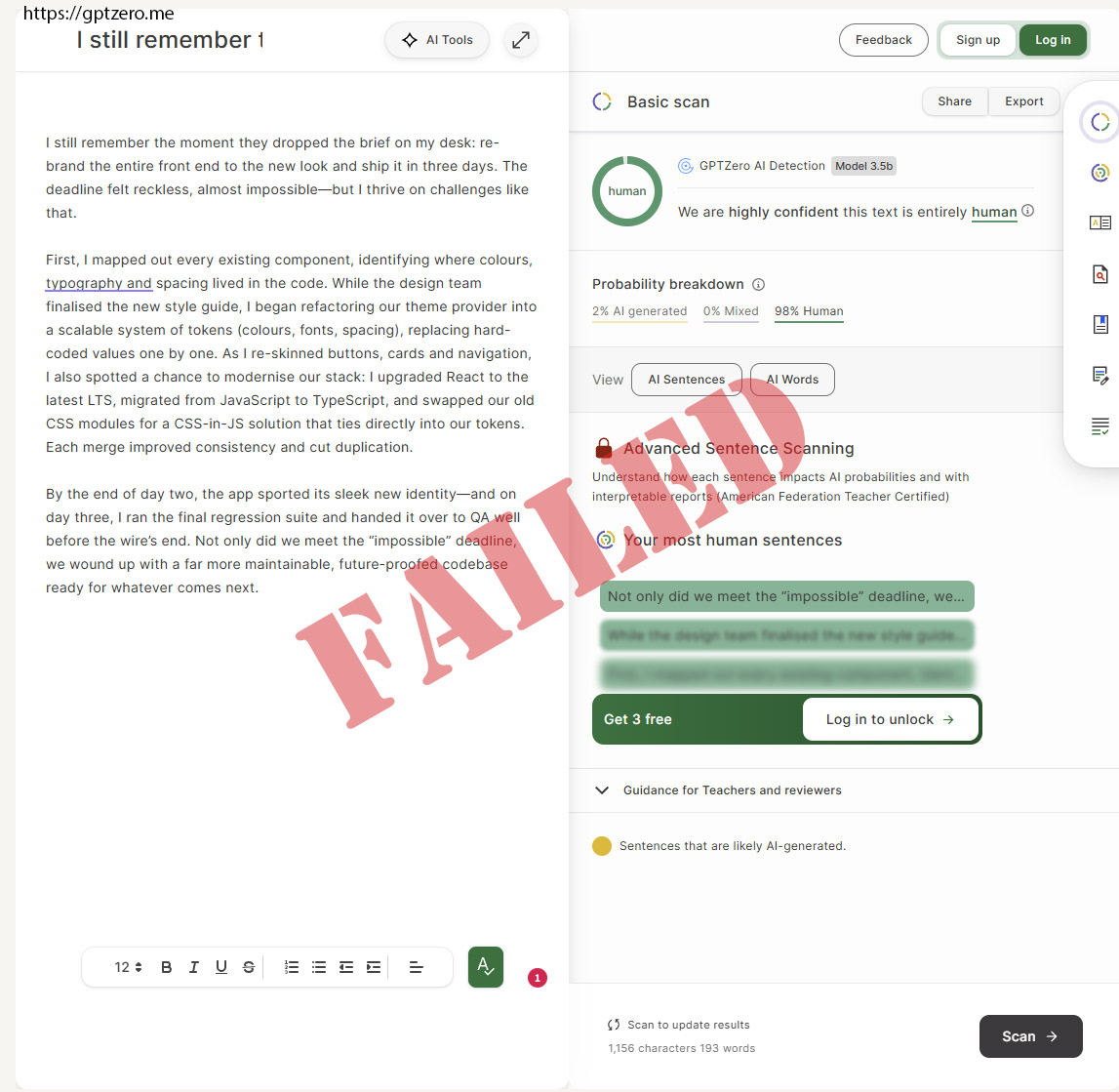

AI has become the new scapegoat. It’s made imperfection the new hallmark of human authenticity, and conversely, perfection the suspicious signature of AI.

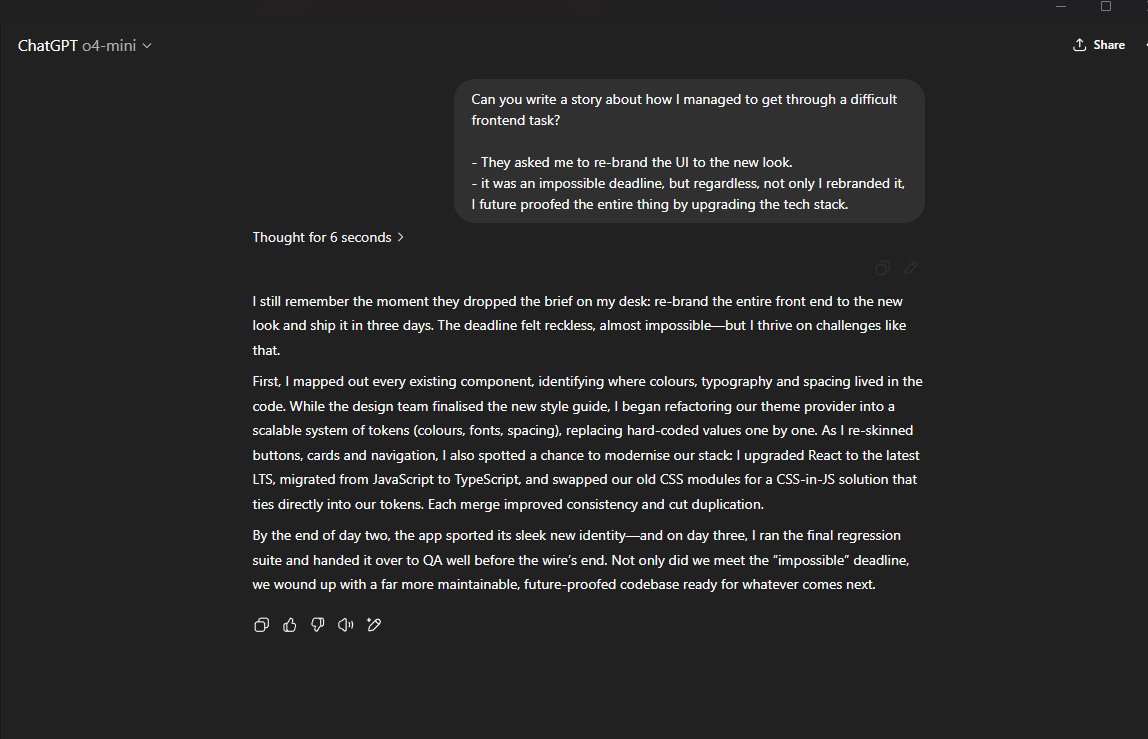

Recently, “some bloke I know” meticulously crafted an incredibly detailed report, evaluating the capabilities of one product against another. As soon as the Product Owner (who he works with) saw the report and noticed an em dash (—), he was immediately called out for “using AI too much and just copied and pasted it without even editing it.”

Here’s the irony: the “dude” entirely wrote the report. No AI was involved. He is meticulous about correcting spelling mistakes in his reports, uses grammar tools to enhance readability—and (a-ha! Em dash!) habitually uses the em dash, even setting an exception in his word processor to prevent it from being corrected to a comma.

This incident highlights a perception issue surrounding AI[1], [2], [3]. There is a growing tendency to attribute any polished, well-articulated, or slightly unconventional writing style to artificial intelligence. Human diligence and a nuanced writing style are suspiciously viewed as machine-generated.

There’s a growing tendency to attribute any polished, well-articulated, or even slightly unconventional writing style to artificial intelligence.

It is rather a bind, isn’t it? The moment a human manages to produce work that is truly polished—devoid of typos, grammatically unimpeachable, meticulously detailed—the immediate reaction is suspicion, not applause. Our hard-won diligence, the very traits we have strived for in reporting, are now twisted into evidence against us.

It is as if our arduous journey to achieve precision and error-free output has ironically rendered us indistinguishable from the very tools designed to assist us. The “human touch” has paradoxically become synonymous with sloppiness, while flawless execution is now considered prima facie evidence of algorithmic assistance.

And, even if the bloke used AI, so what? This readiness to jump to conclusions, often without bothering to understand the underlying process, creates an unfair burden on individuals. It underscores a societal misunderstanding of what AI actually is. This pattern of apprehension is worth examining, because it shapes how people evaluate work and credibility.

Statements like ‘Our company shouldn’t use AI’, or, “You can’t trust what AI say”, typically stem from a limited understanding of how these tools actually function in practice. What they are typically inadvertently revealing is a fundamental lack of understanding of how to effectively use the tool.

Such a stance regularly reflects discomfort with emerging tools and an absence of practical exposure to how they are applied responsibly. An inability to engage with LLMs and AI models signals a closed-mindedness that severely limits an individual’s, and by extension, an organisation’s potential for innovation. It speaks less to the limitations of AI and more to their own comfort zone.

If You’re Judging AI Use by ‘How It Looks’, You’re Doing It Wrong

Managers and reviewers are increasingly asked to assess work that may or may not involve AI. Many default to surface cues: tone, structure, polish, or stylistic markers. This is a mistake.

Well-written work is not evidence of AI use. It is evidence of care, experience, or good tooling. Judging authorship by aesthetics leads to false accusations, erodes trust, and discourages quality.

If you are responsible for reviewing work, here is what actually matters:

- Don’t look for AI-work ‘clues’. Read the entire context of a work or document, instead of judging how “perfectly written” it is or by finding an em dash and jumping to the GPT generalisation. Focus on the substance, not just the perceived polish.

- Evaluate substance, not style. Ask whether the reasoning holds, the data is sound, and the conclusions follow logically. AI cannot guarantee correctness, and humans can still be wrong without it.

- Ask process questions, not accusatory ones. Instead of “Did you use AI?”, ask:

- How was this produced?

- What sources informed it?

- What checks were applied?

Competent authors can answer these questions regardless of tooling.

- Understand that AI use is not binary. Spell-checkers, grammar tools, IDE autocomplete, and LLMs exist on a spectrum. Drawing an arbitrary line based on discomfort rather than policy creates inconsistency.

- Embrace the Tool. AI is a tool, and its effectiveness and ethical implications are largely determined by the human hand that wields it. This means moving beyond fear and embracing informed engagement.

- Demand Competence. AI’s value stems from its ability to amplify human capabilities and boost efficiency. For example, GPTs can make an experienced programmer’s work faster, but in the hands of a novice, they can lead to code bloat or broken logic. The problem is the novice, not the logic.

- Set expectations explicitly. If AI use is restricted, define why, where, and how. Vague prohibitions lead to fear, not compliance.

The goal is not to eliminate tools. It is to ensure accountability. That accountability comes from understanding, review, and dialogue, not from guessing based on polish.

If you want better work, reward clarity and rigour.

If you want responsible AI use, invest in literacy.

Let’s go back to that bloke who wrote the detailed comparison. He was, in fact, specifically asked to do “Research” on these two products. Research.

By definition,

Research is the “systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions…”

…it is never comprised of a mere two paragraphs. Yet, the Product Manager expected a half-arsed Amazon review.

That was not fair. When you ask for research, you should expect a systematic investigation, not a blurb. But because the output was thorough—because it actually met the definition of the requested task—it was deemed suspicious. The manager saw diligence and, blinded by a culture of mediocrity, mistook it for machine generation.

Contrast that with someone who actually uses AI to enhance their human capacity. I have seen a Registered Nurse state that GPTs have significantly reduced her nursing documentation burnout by 90%. She is not simply copying and pasting; she diligently reviews the generated content to ensure its accuracy. AI is not about replacing people; it is about augmenting them.

Consider my own anecdotal experience: I successfully planted a cherry tree, and it thrived, all because I followed AI-generated instructions. For a day, I was a professional Arborist (apologies to actual arborists for momentarily stepping into their domain). This is about relieving people of trivial work so they can focus on the bigger things that matter. It is akin to getting a plaster from the medicine cabinet rather than calling 9-1-1 to get EMTs to dress up my boo-boo.

You hear claims that AI will eliminate jobs or lead to an existential threat. Elon’s fantasy (ugh, Elon) of “AI wiping out the human race” feels borrowed from a Schwarzenegger blockbuster. It is laughable. As someone who understands code and algorithms, I can tell anyone that the “self-aware” nonsense is all but fiction.

The only true concern I have with the usage of Artificial Intelligence models is the concern shared by organisations that genuinely require privacy[4]. These LLMs are often underestimated, blamed for problems and mistakes humans make after using them.

But AI is not to blame. It is a tool, and like any tool, it is neither good nor bad; its impact depends entirely on the user.

Apply Critical Thought[5]. Check yourself

AI has become an easy suspect. When something reads clearly, flows well, or shows signs of care, the reflex is no longer to ask how it was produced, but what tool must have produced it. That reflex says more about our discomfort with polish than about artificial intelligence.

AI does not remove responsibility from the person using it. If anything, it increases it. Tools amplify intent and skill. Informed use leads to better outcomes. Uninformed use leads to errors that are still human in origin.

The real issue is not whether AI was involved, but whether the work holds up under scrutiny. Does it make sense? Is it accurate? Can the author explain it, defend it, and stand behind it?

If we want to use AI responsibly, the answer is not suspicion by default, nor blind trust. It is literacy. Understanding what these tools do, where they fail, and how they fit into human workflows.

AI is not the problem.

Our perception of effort, authorship, and credibility needs to catch up.

…oh, and did you notice what I wrote in my posts’ excerpt? That was 100% written by me, but since I ended it with words like, “It is essential…”, some bugger out there will think I got ChatGPT working on that. 😏

- Can We Really Tell If a Text Was Written by AI? ↩︎

- AI-generated poetry is indistinguishable ↩︎

- The increasing difficulty of detecting AI ↩︎

- When handling classified government or military information, the use of AI is typically discouraged to avoid putting potentially sensitive data or code into a private AI company’s data. This concern is easily mitigated by adopting open-source and self-hosted AI models. ↩︎

- To avoid mistaking competence for algorithms, apply specific heuristics to your thinking. Start with First Principles: strip the work down to its fundamental logic and facts. If the reasoning holds, the aesthetic wrapper is irrelevant. Next, apply Occam’s Razor to invert your default assumption; it is statistically more probable that you are observing a professional’s diligence than a fraud’s conspiracy, so do not project your own limitations (classic Dunning-Kruger trap) onto their expertise. Finally, apply the “So What?” test: if the output is accurate, sound, and solves the problem, the tool used to achieve it is secondary. Be a person of reason who judges the result, not the method. ↩︎